It’s a sunny and pleasant day here in Silicon Valley. A perfect day to chat about the imperfections of AI and the oddities of Breaking Tulips.

Several weeks ago, so long now that everyone has likely forgotten, MIT put out a business survey of generative AI effectiveness, and found that hardly anyone is happy, except the consultants. “Just 5% of AI pilot programs from enterprises contributed “rapid revenue acceleration,” while the majority stalled and offered little financial impact”.

Of course, companies like Nvidia took a brief hit and then promptly went back up again, proof of the resiliancy of this latest Silicon Valley AI Bubble.

Given the wackiness of our current business climate and government, it is no surprise that people are clinging to generative AI as a beacon in the looming economic darkness. There are few opportunities for launching other technology startups as a few huge AI companies continue to suck in the majority of investment dollars and press hype.

New technologies are also a very hard sell in a risk-adverse market. Customers will only buy from extremely well-funded “startups” or well-established companies — if they purchase anything at all. And with the ever-present fears of economic upheaval, nobody wants to issue a PO, unless it’s for a sure thing.

And that sure thing is, of course, generative AI! Why? Because all the press and buzz says it is.

Behind the curtain there is great concern about results. That is why companies like IBM are actually doing a bit better. The assumption is there will be a need for high priced consultants to make generative AI a positive and lucrative business success. This confidence in the consultant pipeline and the belief that generative AI will eventually “get there” is what’s keeping the investment bubble going.

Oddly enough, contrarians are saying generative AI is just another “tulip bubble”. The actual Netherlands tulip bubble occurred from the early 1600s to the 1630’s. After a long period of fascination and investment in tulips by the aristocracy, the merchant class got into the action in a mass of speculation and eventual catastrophic collapse. It’s one of those “case studies” economics students love to pontificate about. So yeah, everything is a “tulip bubble” to some folks.

I’d like to say right now that our AI bubble is not a tulip bubble. If you want to go pick flowers, try crypto.

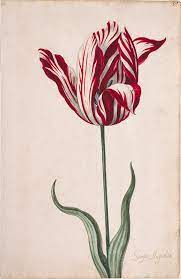

But there is one little piece of trivia about the tulip bubble that I do find applicable, particularly to broad-based LLMs. And that is the investor fascination with Broken Tulips.

Broken Tulips are a stunning flower. Induced by a virus, tulips will unpredictably turn from a humdrum bland solid color to an exciting streaked flaming riot of colors. These tulips were sought after by investors and caught the attention of the masses. Everybody wanted one. Artists painted them. Investors purchased them at huge sums. They were the height of tulip mania.

But a virus riddled plant is not a strong plant. And so it was with these tulips. They all died out very quickly — and so did the investment. According to the Amsterdam Tulip Museum, “Over time, the virus weakens the bulb and inhibits proper reproduction. With each new generation, the bulb grows weaker and weaker, until it has no strength left to flower and withers away.“ Not a good bet for seasonal returns. And since tulips are supposed to bloom every year, a dead plant is a dead loss.

Which brings us to another recent study, in the long line of studies, relating to generative AI LLMs and “hallucinations”, in this case by researchers at OpenAI. In Why Language Models Hallucinate, Kalai, et al. argue that language models are essentially encouraged to “guess” if they don’t know the answer, leading to absurd and false statements. They also state that this problem is persistent and pervasive due to the training and evaluation processes inherent in the process.

Current LLM models are akin to breaking tulips. They’re infected with incorrect assumptions that make them appear smart and decisive. Like a breaking tulip, this confidence inspires the customer to want more and more. In an age of complexity, nothing is more seductive than a decisive answer. And when a model seems to know more than you do, you can stop worrying and thinking and just defer to it. Even if it’s wrong.

Hallucinations popping up again and again are not a good basis for business decisions. Hence the MIT survey results.

Like that lovely infected tulip, the infection is persistent and insidious — to the point the LLM model may become too damaged to rely upon. Kalai, et al. offer no satisfactory cure for this infection. They state, “This ‘epidemic’ of penalizing uncertain responses can only be addressed through a socio-technical mitigation: modifying the scoring of existing benchmarks that are misaligned but dominate leaderboards, rather than introducing additional hallucination evaluations. This change may steer the field toward more trustworthy AI systems.”

In other words, businesses should go back to the drawing board and create their own LLM results based on binary true/false statements, carefully run, so as to mitigate the attempts to provide any non-verifiable answers. Which is how earlier models were typically done.

When a solution is sold as “simple”, telling the customer they now must do a lot of complicated work to make it trustworthy isn’t the best answer. But it’s the only path forward for these customers who are betting their future on generative AI.

Generative AI is not a tulip bubble. But some aspects of it are bubble-like. Given the promise it offers to business, I expect to see curated trustworthy business LLMs which are held proprietary.

However, for those heavily infected models used by the public, we can continue expect nonsense spewed out confidently and wrongly. I doubt most people will notice.