I came across this essay on Silicon Valley’s ascendency. It’s a bit wordy in some places and only abstractly relates to Silicon Valley. But who can resist an article that merges IPR, Gramsci, Silicon Valley investment, and Bretton-Woods.

I was amused, no matter how romantized some of the the assumptions. Come on, we all know that communism was really just another form of kleptocracy in disguise, just like Prosperity Gospel, unbridled capitalism, and all the other scams. It’s the human condition writ large.

Scams work by promising people things they don’t merit nor deserve in return for becoming their trolls, fan-boys, minions, and various minor demons. At least Maxwell’s demons did some undeniably important work, but most of these lesser types from the Stygian Depths reject pile don’t want to work (hence the “merit” stuff I menioned), nor are they part of the in-group (hence the “deserve” part). They’re also non-too-bright as a rule. But they are useful in aiding the ascent to substantial power and wealth, primarily by flooding the airwaves and empty streets with bellowing monsters, which in turn is covered by a lazy press corp as a meaningful “event” which should be taken seriously by “those in charge”.

Technology has certainly brought down the costs of this well-established mechanism. You don’t have to print pamphlets to get attention. You can even more cheaply motivate the mob using facebook ads targeted to any feeble-minded demographic, or pull off in-your-face twitter placement with a word from the Big Twit himself.

Honestly, it makes me long for the good old days of board room shenagins when William and I pitched hard tech companies. And yes, they were just as misogynistic, narrow-minded, and assholish then as now. That hasn’t changed.

It’s just back then there were still rivals, rules, and relationships to manage in the SV investment side. So William and I had a fighting chance. And fight we did. Sometimes…sometimes we made a success — before anyone caught on. Those were amazing times.

Now writers view startups as some kind of historical media retcon — a rather odd combination of Highlander, Fawlty Towers, and The Big Bang Theory (no women allowed, folks, unlike real life). William, who handled acquisitions for Tandem at one point, also had a fondness for Barbarians at the Gate, but that’s East Coast, not West Coast. And despite what folks will tell you, all those hagiographic movies about SV are so ridiculous and boring I just don’t bother.

But historical fiction about SV will continue to be popular, especially with a polisci or econ twist. So go ahead, and imbibe this one, especially the amusing views of open source development and startups:

“Within even the very early culture of Silicon Valley, a distinctive tension could be discerned between the “hacker ethic”—with its commitment to entirely free and open information, born as it was in a university laboratory—and the entrepreneurial drive to protect intellectual property. This was not a superficial short-term contradiction, but a defining productive tension that continues to animate the entire domain of networked and computer-driven social and economic relationships.”

Gilbert and Williams, How Silicon Valley Conquered the Post-Cold War Consensus

On to one of my personal pet peeves — there was no hacker ethic as described by the authors back when we were putting together various technologies for the Internet and Berkeley Unix prior to the early 2000s. The very concept of a hacker having any ethics is so laughable I wonder that any reputable journalist can type the words without gagging. We were in it for the fun, the money, and kicking over apple carts. Anything else someone tells you is a sales pitch.

Not to say there weren’t hackers back then. Of course there were. John Draper, aka Captain Crunch, was one such example. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, one could still get access to all the telecommunications and tech docs in public libraries and, with a bit of cleverness and elbow grease, hack pay phone, computers, and all sorts of primitive networks. Security was an afterthought in those days. Security is still an afterthought now. However, it wasn’t all fun and games. John was always followed around by men in suits and shiny black shoes at conferences, William noted.

Even 386BSD, which through Dr. Dobbs Journal articles and releases birthed the open source operating system (even Linux used the article’s 386 source code supplied with every issue), was based on a very different viewpoint from the present-day common viewpoint of everything “free”. Berkeley Unix had been licensed for over a decade, yet the vast majority of works which encompassed it were not proprietary. It was inevitable that eventually those code remnants would be removed and replaced.

Yes, the copyleft and RMS were talked about a lot back then with the long-awaited HERD OS expected to roll over everything in the universe and then Marxism would prevail! Gosh, I can barely type that while laughing. And yes, they really did believe they were some kind of Second Coming of the Open Source Proletariat before Bernie Sanders came along and stole their thunder.

This invested belief in the copyleft actually allowed Berkeley and us to work quietly. Frankly, no one expected Berkeley to finally get around to removing most of the old version 6 Unix detritus.

Even William’s and my prior company, Symmetric Computer Systems, contributed code on disk drive management. And William and I contributed the source code for the 386 port, making Berkeley Unix actually usable.

During this time, I really enjoyed writing the Source Code Secrets: Virtual Memory book with William, based on the virtual memory system from CMU. The CMU Mach project provided the key in a new approach to a virtual memory system, permitting the jettisoning of the old industrious evaluation virtual memory system of a decade prior. It’s a nice piece of work that is much underappreciated.

And of course, when the unencumbered incomplete release was made public, we got creative and wrote entirely new modules to fill in the missing pieces for the releases.

But working on open source and working on proprietary intellectual property is not antagonistic as the author would state. One of my proudest moments was getting my patents granted for InterProphet’s low-latency protocol processing mechanism and term memory.

The key is understanding what you owe to others and what you owe to yourself.

Berkeley Unix was a long-term project that collected the works of many people. Berkeley handled the release mechanics and integration. Sometimes they did new work, but not always. It was research, mostly paid for by the government. And that means you and me.

William and I did the port to the 386, contributed code, wrote published articles, and devised new work as a research project. While we received no funding from Berkeley, we did have a lot of fun.

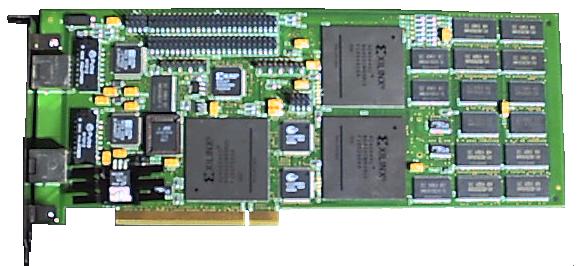

InterProphet, in contrast, was a 1997 startup focused on improvements in latency in networking using a dataflow architecture. Our innovations were funded, we had employees and an office, and we built the prototype and production boards. We developed the drivers and support software. We paid for really expensive proprietary chip design tools.

And we filed patents and held trade secrets. Intellectual property protection was a given in this work. (A bit of advice here: If your engineers decide to deal with bugs in their software by sending source code to the vendor, put a stop to it immediately. It causes no end of problems later.)

We had an obligation to the investors at InterProphet. And we kept our deals with that company. Just as William and I did with Symmetric Computer Systems back in the 1980s. Technology innovation was valued — at least enough so we could get another startup off the ground. It required due diligence and careful maintenance.

The mistake in many “historical” analysis of Silicon Valley innovation lies in conflating the technology innovation of the pre-2000 era with the non-innovative “free stuff” of the post-2000 period. Investment strategies were completely different. Business structures were different. Even financial structures pre and post IPO changed markedly. They’re not comparable.

There is nothing “free” in using FaceBook, or Twitter, or Google News, or Apple Maps, or a plethora of other websites. And that is by design.

These websites and applications are intended to go “viral”. They must lure in an unsophisticated customer and make the site “sticky” so they can be tracked. Gosh darn, that’s all it was and is about. No innovation required. In fact, invention and innovation were derided. As John Doerr noted back then, it was “renovation, not innovation” that was king.

And as the author notes, anything related to manufacturing was sent off to China. No more chip investments. No more hardware investments. No more of that “risky” tech innovation. It had all been done.

I don’t usually call out specific VCs from that time, but John Doerr and Kleiner deserve it for singlehandedly killing an entire generation of technology with a cynical investment strategy. Special mention goes to Google, Apple, and Intel for corralling open source operating system innovation to maintain their profits.

So John and KPCB, and the tech monopolies as runner-ups — I salute you.

People went hunting for content to populate those websites. Youtube for example grabbed the few popular short videos circulating on the web and put them on the site just to appear like it was being used — until it was used through relentless press.

Customer acquisition dollars were high. A flip was six months.

Content was available in many ways. As the printed press conglomerates strove to grab eyeballs, they inadvertently gave their content away while cratering their traditional print advertising dollars. Aggregators glommed onto that content, manipulating the views towards paid ads and “curated” experiences. Video and music content was pirated as well, but entertainment media executives had been down this road many times before, and hit hard with copyright lawsuits.

Databases of many kinds were publicly available as well, from geolocal map data to astronomy datasets. With that richness of information, the sky was the limit for people putting a front-end on the information. And so it is today.

I remember when Amazon was first funded as a bookstore. I bought a book — a Harry Harrison Stainless Steel Rat book I recall. One of the VCs back then gave me the dark side sell at an investment event: It was all about knowing what you look at, what you want, what you need. And putting that in front of you so you buy it. And Amazon takes a cut all the way to the bank. Privacy? Who cares.

It took Amazon six years to a quarterly profit.

Think about that. Six years losing money. When a VC starts demanding quarterly profits, dig up Amazon’s pro formas.